Workload management capabilities are critical to maximizing claim processing time and understanding true hiring gaps. We recommend:

To get started:

First, you want to move people off of tasks when there are too many assigned. If you have a backlog of claims awaiting “Step 1” you will probably want to “right size” the number of assigned employees to that task to only the number needed to work it down within one day. (For later steps, you may have a longer window, but moving claims out of “Step 1” quickly should be prioritized.)

Second, you want to update the accuracy of your underlying data. If you estimated that it would take employees an average of 6 minutes each to complete “Step 1” and they’re consistently not meeting that target (or consistently meeting it faster), then you need to adjust your underlying time estimate accordingly.

“The [Nevada] Strike Force worked with staff to develop a Backlog Elimination Plan to organize team efforts, develop a strategy to address the mounting inventory of unemployment assistance claims, prioritize limited resources, identify additional staff and set out plans to train them. Beginning in September, this plan was updated weekly allowing the team to 1) prioritize resources and 2) create a sequence of activities to support the expedited review, payment or denial of outstanding PUA and UI claims.”1

This exercise can also help you identify opportunities for automation. For example, many states will discover that their current backlog of determinations interviews will take, literally, a decade to work through. This is impractical. Instead, you could replace the majority of manual determinations interviews with electronic surveys like New Jersey did.

Scalable: “Other [success] factors states mentioned include a higher degree of automation (i.e., less labor dependence) in initial and continuing claims functions, and less training needed when moving or hiring staff into the claims-taking area than in the more complex areas of adjudication and Appeals.”2 — National Association of State Workforce Agencies

During the pandemic, many claims processors were forced to go into the office because of the lack of remote computing environments, collaboration tools, training materials, or phones. While the pandemic forced many remote workforce developments in many states, not all are completely remote ready. In particular, many states we interviewed cited partners like AWS Connect and Verizon as mission-critical success factors in enabling hundreds or thousands of employees to operate remotely.

Physical mail continues to play a role in unemployment benefits, including intra-agency mail. Moving to a mail processing system that can scan and disseminate physical mail across the workforce (not to mention send back out physical mail) is a necessary component of being remote ready.

Many states reacted to the pandemic by hiring hundreds or thousands of new employees. This had the opposite of the intended effect — rather than speeding up claim processing, all of the new hires effectively brought things to a halt. All experienced claim processors had to devote all of their attention to training new staff, who couldn’t get up to speed on complex eligibility rules and mainframe computing environments quickly enough. (Not to mention, many state workforces weren’t equipped for remote work.)

As states have tried to hire more staff to address increasing claims volume, most found that they couldn’t train new hires quickly enough. Many report standard training periods of 6 to 12 months. Further, many claim processing roles are legally required to hold certifications and/or years of experience that require 4 to12 years of experience, which is an impossible gap to close on a dime.

In a report to the U.S. DOL, NASW indicates that this training challenge has plagued unemployment for decades:

Training new staff members was both important and a major challenge in many, if not all, states, as evidenced by the number of times state officials brought up training despite the interview protocol having no direct questions about training. Florida officials reported, for example, that training new staff was the biggest challenge they faced in ramping up. Nebraska, which nearly doubled its claims-taking staff as the recession hit, described its training schedule as “intensive.” Rhode Island officials noted that when the number of staff tripled in February 2009, the state faced significant challenges with training. Training was necessary not only for staff coming in the door, but for staff moving among positions, and training staff in more specialized areas could require a significant investment of time. For example, officials in Montana noted the state couldn’t staff up fast enough in the non-monetary determinations area because it takes four to six months to train a new hire adequately. Maine officials said newly hired staff worked on simpler issues at first, but it often was necessary to elevate these staff with little experience to high-skilled positions, such as adjudication, and more training was then required. This was mirrored in Nevada, which received permission to hire additional referees in 2009 to maintain timely appeals performance, but struggled filling positions because they require significant UI experience. Thus, recent hires were often promoted from examiner to adjudicator after just one week of agency experience. Rhode Island officials noted that during 2010 performance improvements in adjudications were smaller than in some other areas because more than half the persons doing adjudications were recent hires with limited initial knowledge of UI and no initial adjudication knowledge. (p 197)

In calmer times, we recommend that states review training requirements and processes to:

It’s a matter of when, not if, state workforce agencies experience another surge in unemployment claims. It’s not realistic for states to maintain human staffing levels at the level needed3 to manually process pandemic-level volumes, all the time.4 Instead, states need to develop strategic “elastic capacity” that can scale up and down with claim volume.

The goal isn't to replace humans with computers. The goal is to protect the rare, experienced eligibility workers so they can focus on complex adjudications and not on tasks like password resets or recertification data entry.

Use your workload management plan to perform a tabletop exercise. In a tabletop exercise, leadership representatives from every business line sit around a table and “act out” a scenario like a recession or a pandemic. Adjust the claim volume and staffing ratios to model how well the agency will perform under various possible scenarios. Measure predicted performance by answering questions like:

Based on recent performance, all states will likely struggle to complete this exercise without issues. Using the tabletop scenario outcomes, you’ll be able to prioritize areas of your program that need elasticity. Increasing elastic capacity requires strategic automation.

States can’t train new employees to process complex claims quickly.5 Therefore, states can’t solve for increased claims volumes with new hires.6 Instead, your team needs to employ automation such that the number of claims that require processing by a human adjudicator doesn’t exceed the capacity of current staff to process them within set timeframes.7

For example: If your goal is same-day benefits payments, then your volume of claims that require a human adjudicator can’t exceed the number of claims your current staff can process in a single day. Otherwise, mathematically, you will have a growing backlog.

Automation doesn’t have to mean a black box algorithm, or even algorithms at all. Instead, agencies can map out their process step by step, and identify where computers can reduce unnecessary burden on highly skilled staff, like:

Automated, self-service password reset is an objectively good idea for every state. Sometimes, a claimant may still need to call and speak with an agent to reset their password. Automating this step will still eliminate almost all of the staff time associated with password resets, while also improving most claimants’ experience and preserving human time for those claimants who really need it.

While automation can absolutely introduce or codify existing biases, thoughtful automation can remove and/or expose bias in a system.

To scale up or down with claim volume, use a central mailing address. Then employ a team or vendor that can adjust to changing volume and charge by the piece.

North Carolina implemented a distributed print solution to expand capacity from 1 million pages per month to 1 million pages per day.

To keep the focus on user experience, we recommend that states start tracking open applications using consistent, claimant-centered metrics. This will also improve their ability to understand and act on the backlog of pending claims that are overdue. Regardless of whether states share this backlog publicly, submit it to U.S. DOL, or just use it internally, shifting to claimant-centered metrics will fundamentally influence the behaviors of the unemployment system — and the team’s sense of urgency.

Here’s how California has started tracking open applications since switching to a claimant-focused approach:

Number of unique claimants with an open claim associated with:

[Any system used in CA for processing UI claims],Customer service messages received electronically or through the call center, ORLegislative escalations

WITH

an earliest open UI/PUA application submission date of > 21 days prior to today

(or > 10 days if earliest open claim is Short-Time Compensation)

- AND -

Appeals by unique claimant:

Lower-levelHigher-level

- AND -

Unopened physical mail, broken down by piece

Defining the backlog in claimant-focused language incentivizes other strategies that are key to improving performance.

This will make it easier to identify a single claimant across all systems. Otherwise, the backlog will appear higher than it really is, a challenge addressed by both California and Nevada8 strike teams.

It’s possible that anyone who hasn’t recertified in the past week may not want unemployment benefits or may have returned to work. However, it’s important to rule out other possibilities, like claimants who don’t understand that they need to recertify, don’t understand how to recertify, or who run into problems with the system, like difficulty printing a form or getting through on the phone.

By tracking those who haven’t recertified, states will be able to measure the ROI of strategies like sending recertification reminders or making recertification easier.

When unemployment is high, legislative offices become overwhelmed with constituent complaints. Since they’re not equipped to process them, this becomes a flurry of hard-to-track emails and phone calls. With claimant-focused data, teams will be able to work more effectively with legislative offices to create a process that reduces the amount of time it spends handling and responding to legislative requests.

In just a few weeks, California built a tool to receive and respond to legislative requests. Each legislative office has its own login to input new constituent concerns and see real-time updates about previous concerns. This allows the Economic Development Department to efficiently handle inquiries, and it allows legislative staff to provide timely and accurate updates to their constituents.

We recommend that the U.S. Department of Labor form a specialized team to:

To respect the intricacies of each state’s system, this specialized team will need consistent understanding of the goal and the skills to query and manipulate data across multiple legacy systems. The team would help states accurately capture backlog data and tweak their existing systems to better support the accurate reporting.

Convening this specialized team would offer a number of benefits, for both individual states and the federal government:

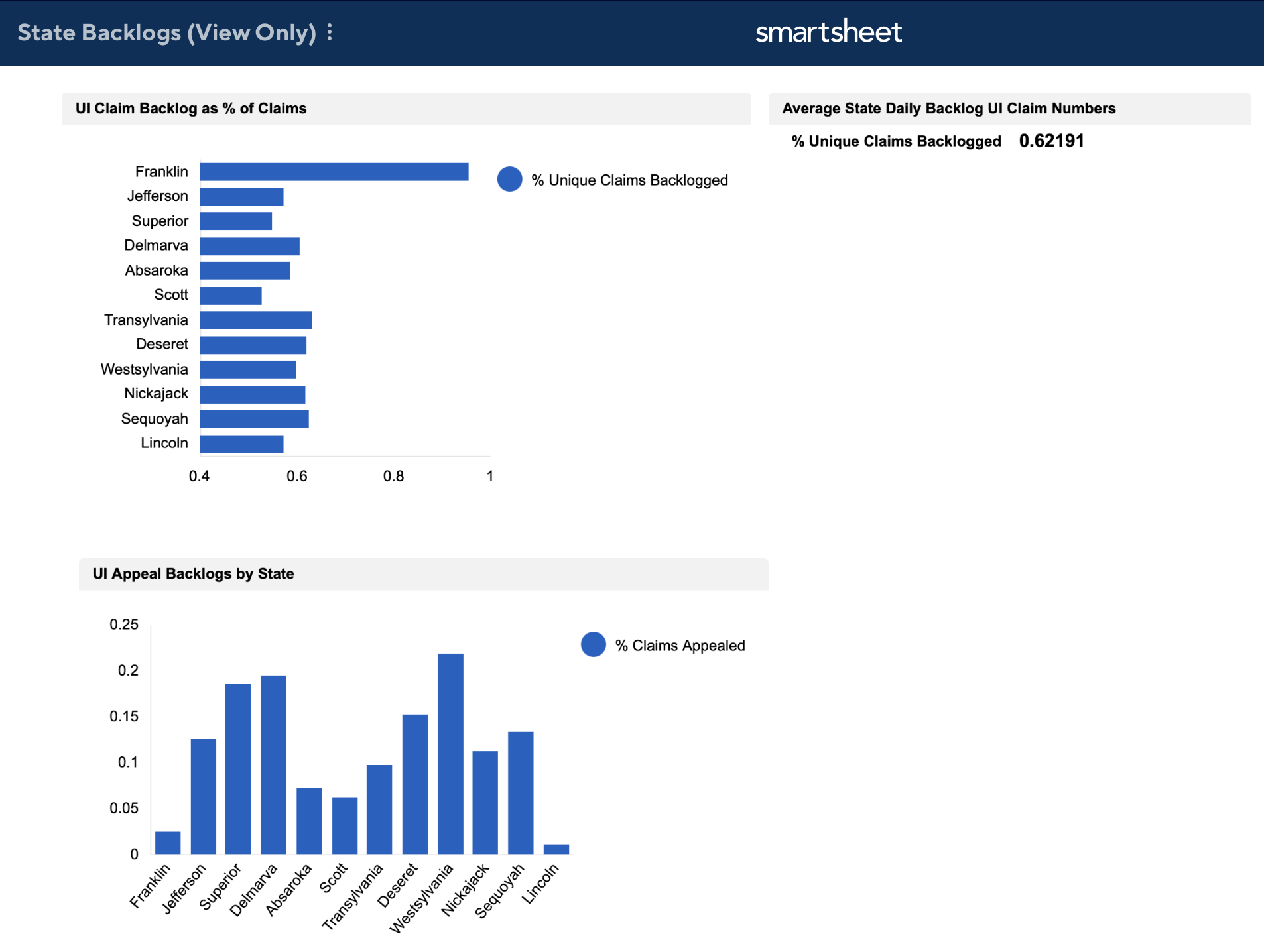

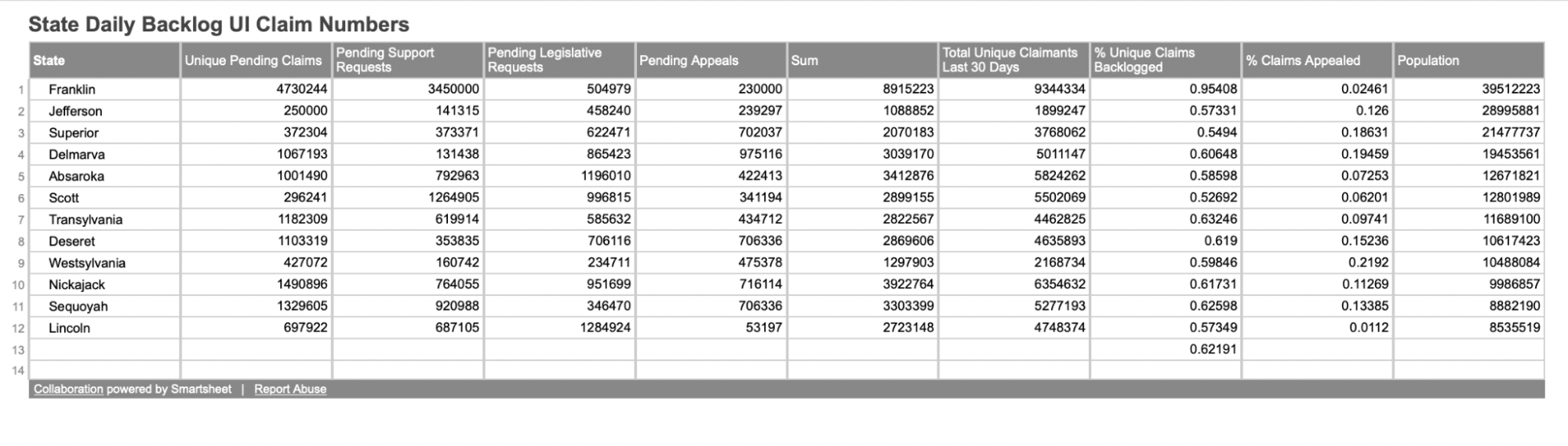

More timely data to focus U.S. DOL’s technical assistance efforts: A central U.S. DOL dashboard that’s updated daily would provide the federal government early warning signs about growing backlogs, and identify states that may require additional technical assistance. To accomplish this, DOL could request that states make their daily backlog dashboard reporting data available in a consistent format (e.g., a spreadsheet with consistent column headings) that can be fed into the central dashboard. This would replace existing reporting measures like first payment timeliness with a more automated and more robust process. We would recommend that the U.S. DOL set an early precedent of using this data to help states, not penalize them.

To see what this could look like, check out the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) example that we built using SmartSheet (a web-based data collection tool that is FedRAMP-certified).

When states begin to break down their workload management tasks, the task that consistently takes the longest with the greatest backlog is determinations. On average, determinations take 30 minutes each, and they must be completed by experienced claims processors.

As far back as 2017, New Jersey recognized determinations as an opportunity area. They were resolving fewer than 10% of determinations within the U.S. DOL timeframe, when the standard was 87%. Unable to close this gap without a time expansion machine, they adopted a creative alternate approach. Today, the majority of claimants who require a determination interview get an auto-generated electronic survey, asking the specific fact-finding questions relevant to their claim.

Claims processors doubled their productivity, shaving an average of 5 weeks off of claim processing time. Using Salesforce as the underlying system for generating and collecting this survey information was another successful strangle the mainframe pattern.

We recommend that every state evaluate its determinations interview process for opportunities where automation, such as a situation-specific survey, can replace the highly labor-intensive and non-scalable manual interview process.

https://cms.detr.nv.gov/Content/Media/Strike_Force_Report_2021_FIN.pdf ↩

https://www.naswa.org/system/files/2021-03/usdolreleasesnaswareport.pdf p189 ↩

“Specifically, more than half the states GAO surveyed reported insufficient staffing, outdated Information Technology (IT) systems, and funding constraints” GAO May 2016 ↩

In the pandemic, claims in 2020 exceeded all claims received in the previous five years combined. States cannot maintain staffing capacities at 5x normal needs. Even in “normal” times workforce agencies have been unable to maintain baseline staffing levels: Nevada experienced 1400% increase and had: “Save for one contract employee, key leadership positions in the Department were either filled with inexperienced leaders or were vacant…Furthermore, hiring of new staff and contract staff was constrained by the need to assign the limited number of seasoned ESD adjudication staff to train and serve as mentors to new hires.” ↩

It typically takes a new claims examiner up to two years to be proficient in interpreting and applying the federal and state unemployment compensation laws and regulations. There were a limited number of qualified staff to handle the sudden and dramatic influx of cases.” - Nevada strike team report ↩

“Two issues of state preparedness to successfully implement the expansion of UI benefits—staffing and system capabilities—have been long-standing concerns underlying many issues noted in prior OIG reports. These issues have been particularly evident in prior periods of increased stress on the unemployment program due to major disasters or periods of significant economic downturn” “Our work related to past funding for emergency staffing under the 2009 Recovery Act showed that states took over a year to spend the majority of funds available for hiring; and at least 40 percent of the available funds were unspent after 15 months” https://www.oig.dol.gov/public/reports/oa/viewpdf.php?r=19-20-001-03-315&y=2020 ↩

https://www.govops.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2020/09/Assessment.pdf ↩

“It was extremely difficult to get clear-cut data on the size of the backlog. For the entire first month of the Strike Force’s existence, data identifying what claims were in what status of review was inconsistent and not reliable. Even today, the case management tools available to DETR are inadequate.” ↩